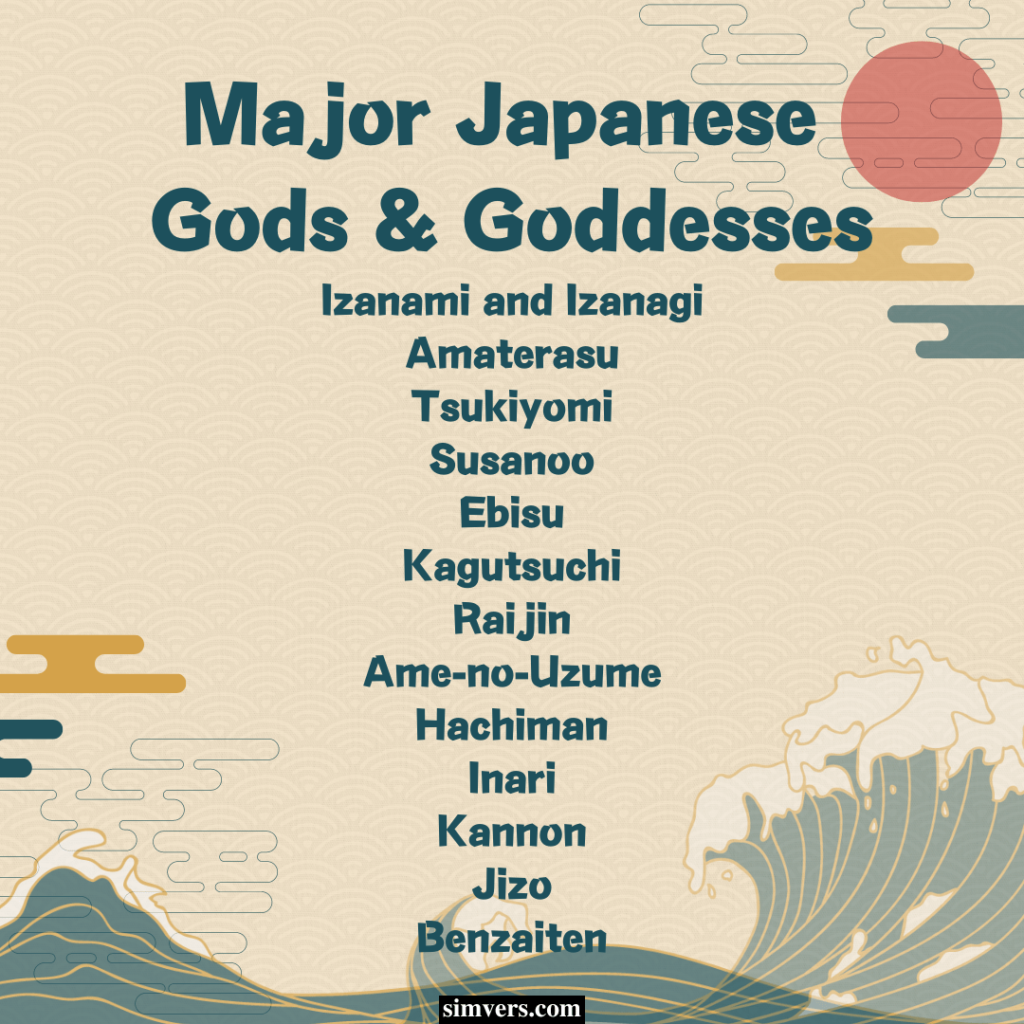

You may be somewhat familiar with the Greek gods and goddesses, but how much do you know about the Japanese gods and goddesses? Over the centuries, Japan has accumulated a unique and fascinating blend of deities. The Buddhist, Taoist, and Shinto religions have a hand in Japan’s most popular deities.

Japanese gods and goddesses range from major creation gods to minor gods of objects or animals. Japanese believers praise these major gods and goddesses for their rule over significant aspects of the past, present, and future and their ability to answer prayers and grant prosperity and luck.

Prepare to read some unexpected and colorful tales of these mighty gods and goddesses. Also, discover Japan’s mythological creation story and why believers worship each of these deities today. Without further ado, below are the major Japanese gods and goddesses!

Izanami and Izanagi

Izanami and Izanagi were creation deities. They were brother and sister, but also husband and wife. They were the last of seven generations of primordial Japanese gods.

Japanese people believed these two deities created the Japanese archipelago. They created three new deities. These three were the storm god Susanoo, the sun goddess Amaterasu, and the moon god Tsukuyomi.

The names Izanami and Izanagi mean she-who-invites and he-who-invites, respectively. Their names may also derive from the Japanese word for “achievement.”

The Kojiki, or the Record of Ancient Matters, is an early Japanese document that describes the myths of the beginning of the Japanese archipelago and Japanese royalty. It describes the kami, the holy deities of the Shinto religion. The kami include Izanami and Izanagi.

So, according to the Kojiki, Izanami and Izanagi received orders from other gods to shape the earth. During the process, they created an island. Through a marriage and intercourse ceremony on the island, Izanami gave birth to other islands that make up the archipelago.

Eight Islands of Izanami:

- Iki

- Tsushima

- Sado

- Ōyamato-Toyoakitsushima (modern Honshu)

- Awaji-no-Ho-no-Sawake

- Iyo (modern Shikoku)

- Oki

- Tsukushi (modern Kyushu)

The holy pair started creating deities to rule each island, but Izanami died while giving birth to the god Kagutsuchi. Izanagi killed this new god out of anger, and Izanami went down to the underworld following her death. Izanagi missed her dearly, so he followed her to the underworld.

However, when he got to the Yomi (the land of the dead), she had already eaten there and could not leave. Unfortunately, Izanagi looked at her and realized she was now a rotting corpse. Izanami was ashamed and sent warriors to chase him as he ran out of Yomi.

Izanagi fled Yomi and blocked the entrance to this underworld so no one could follow him. In anger, Izanami said she would kill 1,000 people every day. To counter her curse, Izanagi said he would create 1,500 people daily.

Now, Izanagi felt impure after visiting the land of the dead. So, he went to a river on one of the islands to take a bath. As he bathed, he produced the three most important deities in the kami: Amaterasu (sun goddess), Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto (moon god), and Susanoo-no-Mikoto (storm god).

Although Izanagi appointed Susanoo to rule over the seas and storms, Susanoo didn’t live up to his expectations. Unfortunately, Izanagi banished Susanoo, and this deity doesn’t appear in the Kojiki after this part of the story. The other two of these three child gods go on to rule their respective territories.

Amaterasu

Amaterasu is unofficially the primary deity of the Japanese Shinto religion. Her name translates to “shines from heaven,” which is certainly fitting for the goddess of the sun. She’s the ancestor of the Imperial House of Japan, which includes the Emporer and his family.

So, Amaterasu was very significant to the Japanese. One of Shinto’s holiest sites is a temple in her honor, the Grand Shrine of Ise. She’s also part of many Shinto shrines across Japan.

The Kojiki, as mentioned, says that Amaterasu was born when Izanagi washed in a river. However, there is a conflicting legend. In the Shoki text, Izanagi produced Amaterasu when he held a bronze mirror with his left hand.

Amaterasu had an eventful run-in with her banished brother, Susanoo. He came to say goodbye to her, but she challenged his authenticity. However, Amaterasu ultimately accepted him despite his subsequent terrible behavior.

During this encounter, Amaterasu produced several gods and goddesses. She kept the males, and she gave the females to Susanoo. At one point, Amaterasu was so furious with Susanoo’s turmoil that she shut herself inside a cave, causing total darkness in the heavens and on earth.

As Amaterasu hid inside the cave, other gods joined forces to figure out how to get her out. They decided to trick her by telling her another goddess, greater than her, had appeared. This successfully lured Amaterasu out of her cave, and the other gods sealed it shut so she could not go back in.

Therefore, Amaterasu’s presence restored sunshine to the world. Since Susanoo caused all this mayhem, the other gods banished him. Fortunately, he went to another Japanese island, where he met his future wife.

Later, Amaterasu gifted her grandson rulership of the earth. Her grandson is allegedly the ancestor of the first emperor, whom the Imperials claim relation to today.

Tsukiyomi

Tsukiyomi was the second of the three divine children born of Izanagi as he bathed in the river. Tsukiyomi is the mood god. His name is a combination of the Japanese words for “moonlit night” and “looking.”

Historical sources imply that Tsukiyomi is male, but scholars are not certain. There isn’t much material about this major Japanese god. There’s one story of him killing the goddess of food because he disliked how she prepared his meal.

After Tsukiyomi killed the goddess of food, his sibling goddess, Amaterasu, was furious at him. She was so angry that she moved to a different part of the sky, so she didn’t have to look at him. And that’s why, according to Japanese myth, the sun and the moon are so far apart in the sky.

Susanoo

Susanoo entered the physical realm when Izanagi took his bath in the river after he visited the underworld. According to the Kojiki, Izanagi produced Susanoo after washing his nose in the water. After his birth, Susanoo failed to succeed in his duties to rule over the seas and storms, so Izanagi banished him.

Ebisu

Ebisu (also translated as Webisu or Hiruko) is the god of fisherman and luck. He’s one of the Seven Lucky Gods in Japanese tradition. He’s the only god of the Seven without any influence from Buddhist or Taoist ideas.

In the Kojiki, Izanami and Izanagi’s first child was Hiruko (Ebisu). However, Hiruko was deformed, so they expelled him. He had to learn to fend for himself in the sea until he washed ashore.

Therefore, some Japanese communities consider any driftwood or other things that wash ashore to be signs of Ebisu. This lucky god has three temples and shrines in Tokyo.

Ebisu also has the title of the “laughing god” because he survived and learned how to thrive despite the hardships he faced as a baby. Statues or paintings of Ebisu show him wearing a tall hat and holding a fishing rod and a sea bass. In Japanese fugu restaurants, Ebisu is a common theme.

Fishermen admire Ebisu and pray to him before setting sail. They praise him for taking care of the ocean and fish. In Japanese tradition, people believe Ebisu is angry at whoever pollutes the ocean.

Ebisu has a festival in Japanese culture. Japanese people celebrate him during the tenth month of the Japanese calendar, January. It’s a trendy five-day festival full of dancing, lucky rice cakes, and other festivities.

Kagutsuchi

Kagutsuchi has many popular cultural references in modern-day Japan thanks to his fame as a mythological deity. If you recall the story of Izanami, Kagutsuchi’s birth caused her death. The father, Izanagi, cut off Kagutsuchi’s head in a rage.

Izanagi’s rage didn’t end there. After cutting off his son’s head, he cut up his body into eight pieces. Those pieces turned into eight fiery volcanos and produced even more gods.

So, what makes Kagutsuchi’s birth and death so crucial to the Japanese? In Japanese mythology, Kagutsuchi’s birth symbolized the end of the world creation story. And at the end of the creation story begins the story of death.

A Japanese record called the Engishiki tells another tale of Kagutsuchi, the god of fire. In this story, Izanami gave birth to another child, a water god. Izanami told this water god to quench the fires of Kagutsuchi if he became too destructive.

Today, many Japanese people worship Kagutsuchi. He’s the deity of blacksmiths. Many shrines throughout Japan are in his honor.

MORE:

- Jesus’ Birth

- Is Jesus God

- Non-denominational Churches

- Norse Gods and Goddesses

- Old Testament vs New Testament

Raijin and Fūjin

Raijin is the Thunder God. Usually, he’s side-by-side with Fujin, the god of wind who was there when the primordial gods created the world. Raijin is a fierce and mighty god, ruling over thunder, storms, and lightning.

Stories of Raijin

Raijin was born out of the rotting corpse of Izanami after Izanagi went to see her in the underworld, Yomi. Izanami sent Raijin to chase after Izanagi as he ran out of the underworld. Raijin was also quite the mischievous god.

The Thunder God caused so much damage from one storm that the God Catcher went out to capture him. When the God Catcher asked Raijin to end the wild storm, Raijin just laughed. Eventually, the emperor of Japan forced Raijin to end the destructive storm and only let him bring prosperous rain to the lands.

Another legend tells how Raijin defended Japanese territory from the invading Mongols. Raijin used the power of a great storm against the Mongol enemies. As a result, they were driven off and defeated.

Stories of Fujin

So, who is Fujin, and why is he often portrayed with Raijin? For starters, Fujin is Raijin’s sibling. Fujin looks quite terrifying, just like his brother.

He carries bags of wind, which he unleashes to add to the turmoil of Raijin’s storms. Fujin escaped the underworld after his birth with his brother Raijin, and the two were nearly inseparable afterward.

Fujin’s image may have been influenced by the Chinese wind deity Feng Bo. Fujin is green and looks like a demon. He always bears a wild, aggressive stance that intimidates even nonbelievers.

Ame-no-Uzume

In the Shinto religion, Ame-no-Uzume is a popular goddess with many shrines. She’s worshipped today by loyal believers for her contributions to the world. She rules over dawn, dancing, meditation, the arts, and celebrations.

Remember the story of Amaterasu hiding in the cave? Well, Ame-no-Uzume was pivotal in getting her to come out so sunlight returned to the world. Ame-no-Uzume cleverly positioned a mirror outside the cave so Amaterasu would come out to see who this new goddess was.

In another tale, Ame-no-Uzume took Amaterasu’s grandson down to earth. Along the way, another god blocked the pair. Ultimately, Ame-no-Uzume fell in love with this other god, and the two lovebirds married.

Hachiman

Hachiman is the Japanese god of archery and war and contains elements from Shinto and Buddhist religions. His duty is to be the holy guardian of Japan and its inhabitants. Although doves generally symbolize peace in today’s world, the dove is the symbol of this god of war.

The Shinto religion recognizes Hachiman as Emperor Ojin, who ruled over Japan in the 3rd-4th centuries. In ancient times, farmers worshipped Hachiman as the god of agriculture, but this god evolved. The samurais worshipped Hachiman because he judged their fate, protected martial arts, and claimed battle victories.

Hachiman shrines are one of the most popular shrines in Japan, after the Inari shrines. The most famous Hachiman shrines are located in Kyoto, Oita, Fukuoka, and Kamakura. Allegedly, each Hachiman shrine was built based on visions that Buddhist leaders or the Emperor had of the Japanese gods.

Inari

Inari Ōkami is the Japanese god or goddess of rice, sake, foxes, tea, and agriculture. This deity also rules over worldly success and is, of course, one of the main deities in the Shinto religion. Followers have worshipped Inari since the first shrine for this deity appeared in the 8th century AD.

Inari’s popularity grew up until the 16th century. Believers honor this deity for its protection over blacksmiths and warriors. Today, more than one-third of Japan’s Shinto shrines are for Inari.

According to the legend of Inari, she first appeared as a goddess who came down to the new land of Japan, riding down from the heavens on a white fox. At that time, there was a great famine in Japan. So, Inari helped by bringing grain for the inhabitants.

Inari’s name comes from “carrying rice,” which is fitting as it was her most admired act. As more people began worshipping Inari, her role as a deity grew, and people worshipped her for much more than rice and agriculture. She became a general symbol of good luck and prosperity in finances, life, and business.

Kannon

In the Japanese-Buddhist pantheon, Kannon is the Goddess of Mercy. She’s extremely popular in Japan, and you can see her in many forms. Her proper Japanese name is Kanzeon Bosatsu.

She usually appears thin and feminine or androgynous. She’s a Bodhisattva who can achieve Nirvana, but unlike Buddha, she does not choose to reach Nirvana because she is so compassionate toward those who cannot. She’s enshrined in many Japanese temples as a way of worship and praise due to her many miracles.

Kannon’s origin is in India, and her character was likely a mix of Buddhist and Taoist goddesses. Interestingly, some statues of Kannon feature 1,000 arms. Another popular portrayal of Kannon has eleven faces.

In 17th-century Japan, Christianity was outlawed. However, some Christians there wished to secretly practice this new religion and pay tribute to Jesus’ birth. So, a “Maria Kannon” statue was built, featuring the Virgin Mary in disguise, holding the baby Jesus.

Some Japanese go on temple pilgrimages to honor Kannon. They visit 33 of her temples, representing Kannon’s 33 manifestations. They visit these temples during a country-wide journey all over Japan.

Jizo

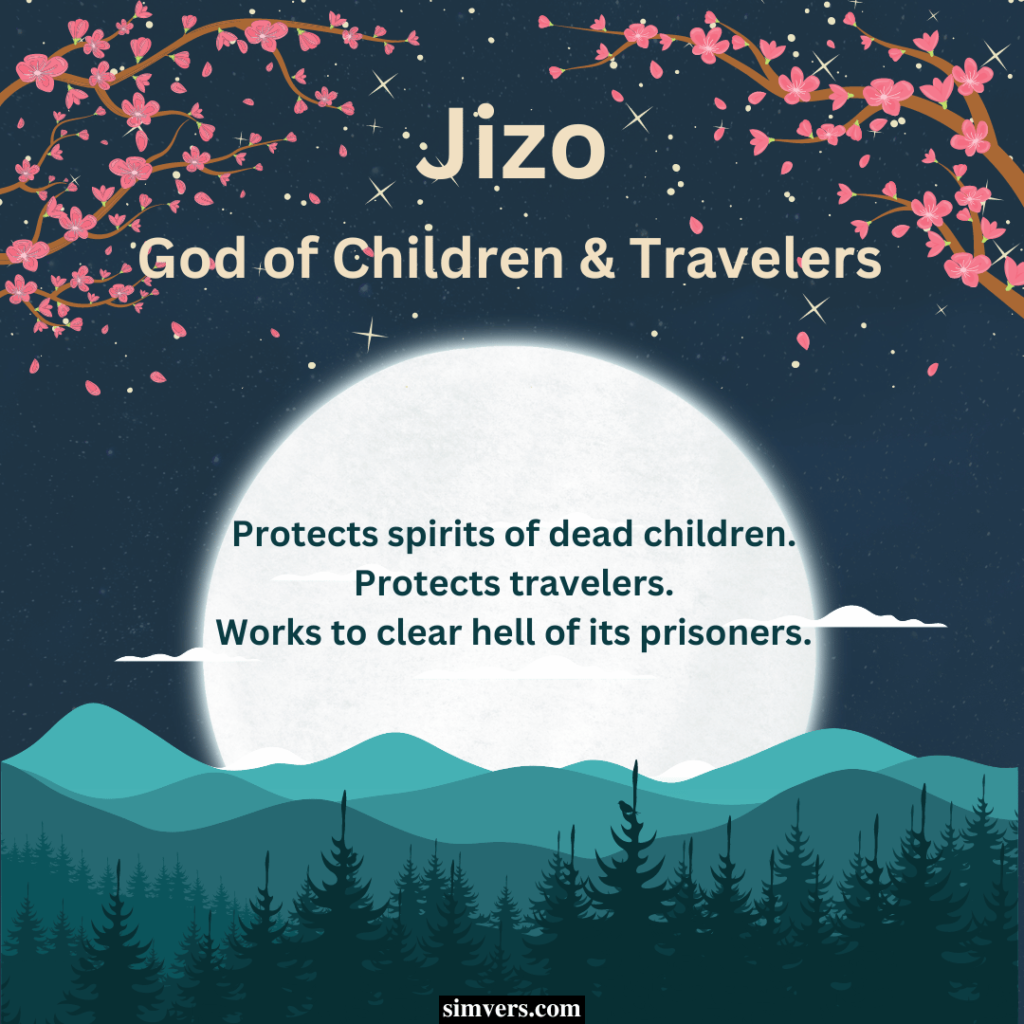

Jizo is the popular Japanese god who protects children and travelers. Jizo statues are made of stone, which is believed to have special spiritual powers of protection. Jizo Bosatsu is a deity known for his gentleness and patience, and his statues can be overgrown with moss or other natural elements.

Another duty of Jizo is to protect the spirits of deceased children. According to Japanese mythology, children who pass away before their parents can’t gain passage to the afterlife. So, they spend their spirit days building stone towers to gain permits to pass over the river that leads to the afterlife.

If you build stone towers by a Jizo statue, you help these spirit children by reducing their workload. Travelers in Japan build small stone towers whenever possible in honor of those children who have passed. With Jizo’s help, they will soon be able to cross into the afterlife.

Like Kannon, Jizo is a Bodhisattva. As you can see, his nature is just as gentle and compassionate as Kannon’s, so he pushed Nirvana aside for the chance to help the less fortunate. He vowed to forego Buddhahood until all forms of hell were cleared of their inhabitants.

Jizo has Buddhist roots and has been worshipped in Japan and China over the centuries. Jizo memorial sites honor travelers who passed away during their travels. This kind of deity also safeguards the spirits of babies who pass away before birth.

Benzaiten

Benzaiten is the goddess of all things that flow. This includes speech, the arts, learning, and music. She’s also known as Benten.

So, what are this eloquent goddess’ origins? Her roots are tied to the Hindu goddess Saraswati, who rules over speech, the arts, and learning. Some of Benaiten’s traits come from the goddess of warriors, Durga.

A Japanese Buddhist monk named Kokei wrote tales about this goddess of flow. He wrote that she was the third daughter of Munetsuchi, a great dragon king. His stories convey her significance and power and depict the history of her shrines.

The Japanese began worshiping Benaiten in the 6th century after reading about her in a Buddhist text called the Golden Light Sutra. In medieval times, she was merged with other goddesses such as Kisshoten and Ugajin. Also, since Benaiten was a water goddess, she was associated with snakes and dragons.

In the Shinto religion, she’s a female kami. Due to her popularity in Japan, she has many shrines across the country. The most popular are the Three Great Benzaiten Shrines in Sagami Bay, Lake Biwa, and Itsukushima Island.

Conclusion

In summary, these major gods and goddesses have significantly impacted the traditions and culture of the Japanese people. In the Shinto religion, these deities are worshipped for the phenomenal areas of life they rule over. The people’s dedication to these deities is evident in Japan’s numerous shrines, temples, and festivals that are held to this day.

MORE:

- Roman Catholic vs. Lutheran

- Roman Gods & Goddesses

- Bible about Suicide

- Best Order To Read The Bible

- Why Does God Hate Me?